Podcast by Daniel Barwick

Welcome back to the mortar board this week. I’m going to talk a little bit about the various proposals that are before the American public for forgiveness of student loans. There seems to be clearly a lot of interest in the subject.

Want to hear this podcast in its original audible format? Click below! Otherwise, just scroll down to keep reading.

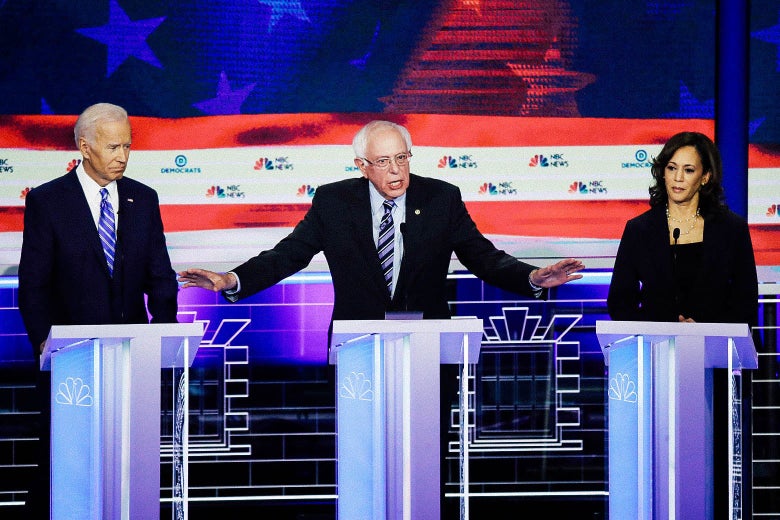

This week I posted on my Facebook page a link to a New York Times article about the various proposals that the Democratic candidates have put forth for the forgiveness of student loans. And then two days during the week that I’m recording this podcast, there have been two democratic debates. (There were two of them because there were 20 candidates that qualified to be on the debate stage, and they couldn’t do 20 candidates at once. So they randomly divide them into two groups and allowed them to debate.) And of course, it’s interesting to consider the proposals that have been raised and what their prospects for success at addressing or solving a problem are.

The response to my Facebook post was very strong. I received plenty of comments on the post, and then I also received many emails from people who wanted to have an offline conversation about the topic. And then of course people asked me also to talk about it on this podcast, because they thought that it would be a good and timely topic for the podcast.

I’m intensely interested in the subject. Most people don’t really understand the connection between student loan debt and other aspects of education, and how it’s affecting other aspects of education. So I’m really interested in talking about this, and I thought I would devote this podcast to that.

First, it’s worth taking a moment to talk about the sheer size of America’s student loan “problem” or “debt,” depending on how you look at it. I won’t disguise for a moment that I think the problem is real. The total debt is now about $1.6 trillion. Millions of people are in default. Many young people graduate from college or from graduate school facing payments that restrict them financially very significantly and restrict their ability to buy homes, or even to start families. (This has actually had an upside, that some employers now compete for employees by giving them the perk of a potential loan repayment benefits.)

There’s some data that suggests that the total amount of the average student’s debt load is not necessarily increasing. It may actually be declining, slightly adjusted for inflation, but I’m not going to talk about the average debt load problem because it’s already significant. And so even if it continues or modifies slightly, the actual problem remains, which is that people have a type of debt when they graduate from college that the vast majority of people did not have a several decades ago when they graduated from college. So what is the average debt load? Well, for students who are just receiving bachelor’s degrees, the average debt load of graduation was about $30,000 in 2015 and 2016, which actually isn’t all that different from the previous years.

Although it adjusts very slightly, there’s a reason for thinking that this amount is not changing significantly, which is that it’s not clear that people can actually borrow any more money than they’re currently borrowing. The thought is that most students are actually currently borrowing the maximum that they can borrow under the federal loan programs. It’s important to remember as well that it’s not just students who go into debt to go to college. Their parents go into debt too. So in 2015 and 2016, the parent’s average debt load at graduation for federal plus loans was $33,000. That’s very significant. It’s just amazing to think that what’s happening is that simultaneously students and their parents are taking on debt in order to pay for the student’s college.

It’s important to understand that that’s just undergraduate school. One of the biggest causes of student debt is actually graduate school. About 40% of loans are taken out to attend graduate or professional school, a master’s, PHD programs, Law School, business school, medical school. So why does it affect the numbers so much? Well, frankly, graduate school is more expensive, and an interesting fact that most people don’t realize is that unlike undergraduate, graduate school does not have the same kinds of borrowing limits that undergraduate has, the borrowing limits that the federal government imposes on undergraduates. So people can borrow far more money, for example when they can go to a graduate school in another state. They don’t receive any kind of in-state break. The tuition is high. There is a cost of living, books and so forth. I did this myself, when I went for my master’s degree at the University of Iowa. I had relocated to Iowa from New York, and I was not a resident of the state of Iowa. If I’d been a resident, I think there would have been a break, but there wasn’t because I was from out of state and I borrowed more because I was attending graduate school and I was doing it as a non-resident.

There are problems that are inherent in all of the proposals that have been raised by the Democratic candidates and I should make clear two things up front: First, this isn’t a political podcast. I’m not arguing for a particular political position or advocating for a particular candidate. And second, I commend anyone who is trying to think seriously about the problem of high cost and high borrowing and education because the high cost part of the equation is important. The cost of education in the last four decades has exceeded the core rate of inflation reliably every single year. This means that the cost of borrowing to purchase that education has gone up as well. In this podcast, I’ve talked about a number of the contributing factors, that range from regulations that are expensive to comply with, to the need to create facilities that students want but are of dubious educational value.

This week, Senator Bernie Sanders proposed canceling all $1.6 trillion of outstanding student loan debt in the United States. I think he did this because Senator Elizabeth Warren had previously proposed canceling $140 billion of the debt, and obviously you don’t get anywhere by just repeating the policy positions of someone else. And so I think he wanted to get people’s attention. Actually I think that he’s genuinely concerned about the debt issue, but there are serious problems with any plan that’s being proposed that would eliminate debt. Let me talk for a few minutes about the kinds of problems that arise when you try to simply cancel debt for the specific purposes for the targeted expenses that these candidates have proposed.

It’s important to remember that these proposals are typically coupled with proposals for making all undergraduate programs at public colleges and universities free, which reduces the need for borrowing. Equally important to remember is that doesn’t actually eliminate student debt. It doesn’t at all. And here’s why. First, remember that most student loan debt isn’t taken out to attend undergraduate programs at public colleges. That’s not what most people are borrowing for. If you look at the data, what you’ll find is that it comes from people attending for-profit colleges and private colleges. And as I mentioned before, graduate school. You certainly don’t need me to tell you how expensive private colleges are to attend. And in fact, as I’ve discussed before on this podcast, even though private colleges do have a discount rate, that is, they’re rarely charging everyone the published tuition so that they’re offering some type of scholarship, the fact is the net amount that the student still has to pay can be considerable. And it’s not just that private colleges are expensive; it’s that because public colleges are cheaper, people simply have to borrow less to attend them, which means that if they choose to go to a public college, they’re going to borrow less by the time they leave because the overall cost was less. So their resulting debt load is less.

So the first problem with the proposals to forgive student loan debt is that they’re actually targeted, not at sort of the worst offenders (God, I don’t like to use the word offenders); the worst examples of student loan borrowing, they’re actually targeted at the lowest examples of student loan borrowing. People go to a public college, and because they went to a public college, they’re typically borrowing less than people who chose different avenues for their education.

A second problem is even worse. Remember that the majority of student loans don’t come from public undergraduate colleges. They come from private colleges or graduate schools. The New York Times, in their story “Canceling Student Loan Debt Doesn’t Make Problems Disappear,” puts it the following way: Because most student loan debt is actually result of private colleges or graduate schools, “this means that the day after Senator Sanders hits the reset button as he put it in the news conference, the national student debt odometer would rapidly begin spinning again. Will those later debts be forgiven to? If not, his plan would create a generation of student loan lottery winners with losers on either side. People who had already paid back their loans would get nothing. People with future loans would get nothing. People with debt on the day the legislation was enacted would be rewarded.”

So if we’re thinking about the consequences of these kinds of plans, which basically just cancel out debt, ultimately, you’ve got to account for ticking off the people who had already paid back their loans, who’d get nothing. And I can tell you that when I posed the question online about these proposals, that was one of the very first things that people raised, which is that, “well, you know, I worked hard, I paid back my student loans. Why should somebody else just get a free ride?” I’m actually, an example of that. So I don’t have any student loan debt. When I left graduate school, I did have student loan debt. I paid it back over a period of years. It was burdensome to do that and nobody helped me with it. So of course, now people who have paid back their debts are asking, well, if this was possible to do, why is it happening now? That’s, I don’t think that’s a good argument, but I would say that it’s a natural human response.

There’s a second issue there, which is that once you begin to forgive debt, you’re going to have some people, some considerable number of people, who believe that that will happen again, and they may borrow on the basis that, that it will happen again. If you’re considering a car loan and a every five years or so, the federal government forgives all car loans and you think, well, they’re due for another round of forgiveness. The fact is you might take out a larger car loan than you would have otherwise. Notice that if this happened, the providers of the education also have an incentive to charge more for education because they may also believe that at some point the loan is going to be forgiven. Remember, they get paid, the school doesn’t loan the money, so they get paid immediately when the student borrows the money from some financial institution. What happens then of course is that the school has an incentive to charge a lot of money, more money than they’re charging now. Why? Because of course they know that the student will borrow more money because the student believes that the loan will be forgiven.

Finally, it’s important to understand that these proposals don’t actually make college cheaper. They just make it cheaper for the student. In fact, when you do that, when you transfer the cost from the individual to a large group, it’s likely that you’ll simply make it more expensive under all of the plans under consideration. It’s not as if the banks are simply told to take a hike. The banks are paid back, they’re paid back with taxpayer money, so the education that the student previously paid for is now paid for by everyone. Why is this important? It’s because the real underlying issue, which is not simply high borrowing, it’s high cost, is unaddressed without tackling the issue of why higher education costs so much in the United States. The fact is that somebody will still have to pay a premium for the education that students attain here. Student loan debt is not just an indication of people’s willingness to borrow money. It’s also an indication of the ease with which people can borrow student loan money. Because of course people can borrow student loan money without collateral because the loan is guaranteed in many cases by the United States government. But finally, the most important thing is that it’s an indication of the underlying cost of the education itself.

High borrowing of anything, whether it’s cars or houses or education, means that the thing that was purchased that caused the high debt was expensive to begin with. That’s the conversation that we are supposed to be having as a country. But in fact what I see candidates doing is talking about the immediate problem of the voter, which is that I have to write this check for my student loan every month. I understand the desire to solve people’s immediate problems, but in fact the proposals that have been put forth for solving that problem would, in my opinion, simply cause that problem in the future for other students and in actually accelerate that problem by driving costs higher and higher.

So what is the solution? Well, I would suggest that the accreditors of colleges, which have sort of the ultimate authority for whether those colleges continue to exist in most cases should have stricter standards for the value that the college is providing right now. It’s true that accreditors do look at default rates. They do examine, the success of graduates and that sort of thing. But the fact is that those standards could be more and more stringent. And in my opinion, schools are not being held to task about the value they are providing. I think that accreditors are actually starting to do this more and more rigorously, but there is a long, long way to go. Ultimately, I hate to use words like “efficiency” because efficiency and education don’t always go together perfectly. But the fact is that what we need is a system that provides greater value for the money. Now, a system that provides greater value for the money can also be a system that provides the same amount of value because many institutions of higher education provide excellent value or excellent education. But I would argue that in some of those cases, the cost is simply too high. So the real challenge is to figure out how to provide the quality education that the US is known for, while at a cost that does not require people to mortgage their futures.